Monolith vs Microservices

In the ever-evolving landscape of software development, the choice of architecture can make or break a project.

It’s not merely a technical decision but a strategic one that shapes how efficiently a team can build, scale, and maintain an application. Whether crafting a simple tool or a complex system, the architecture selected lays the groundwork for everything that follows.

The architecture chosen influences not only how software is built but also how it grows and runs over time. A misstep can result in sluggish performance, tangled codebases, and frustrated teams. On the other hand, the right choice can streamline development, support seamless scaling, and make maintenance easier.

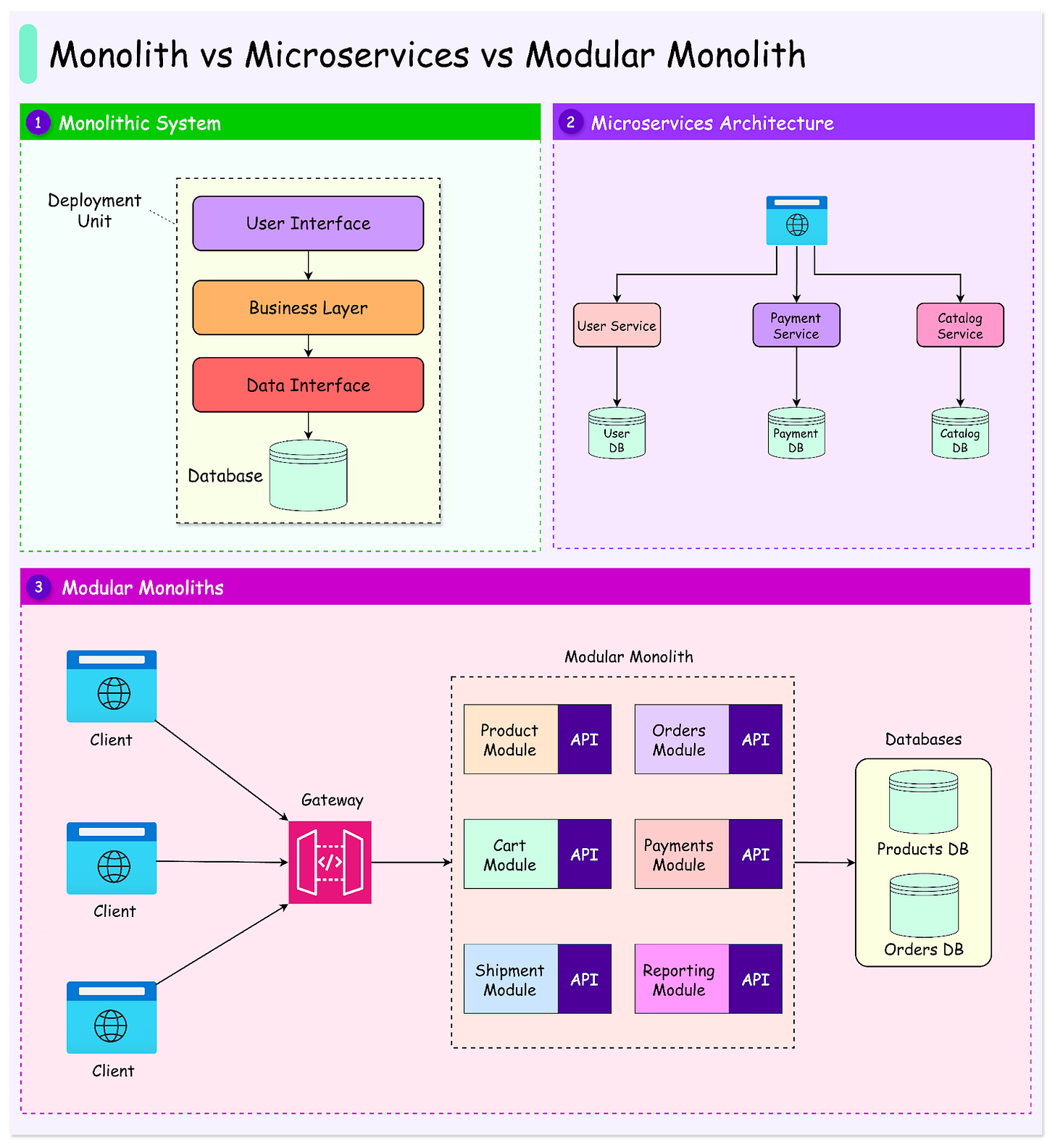

In this article, we explore the three key architectural styles: Monolith, Microservices, and Modular Monoliths. Each offers distinct approaches to structuring software, with unique benefits and challenges.

We’ll also examine the strengths and weaknesses of each approach, from the ease of a monolith to the resilience of microservices and the balanced design of a modular monolith. We’ll look at scenarios where switching from one architecture to another makes sense, equipping us with practical insights for navigating these critical decisions.

[

Monolithic Architecture

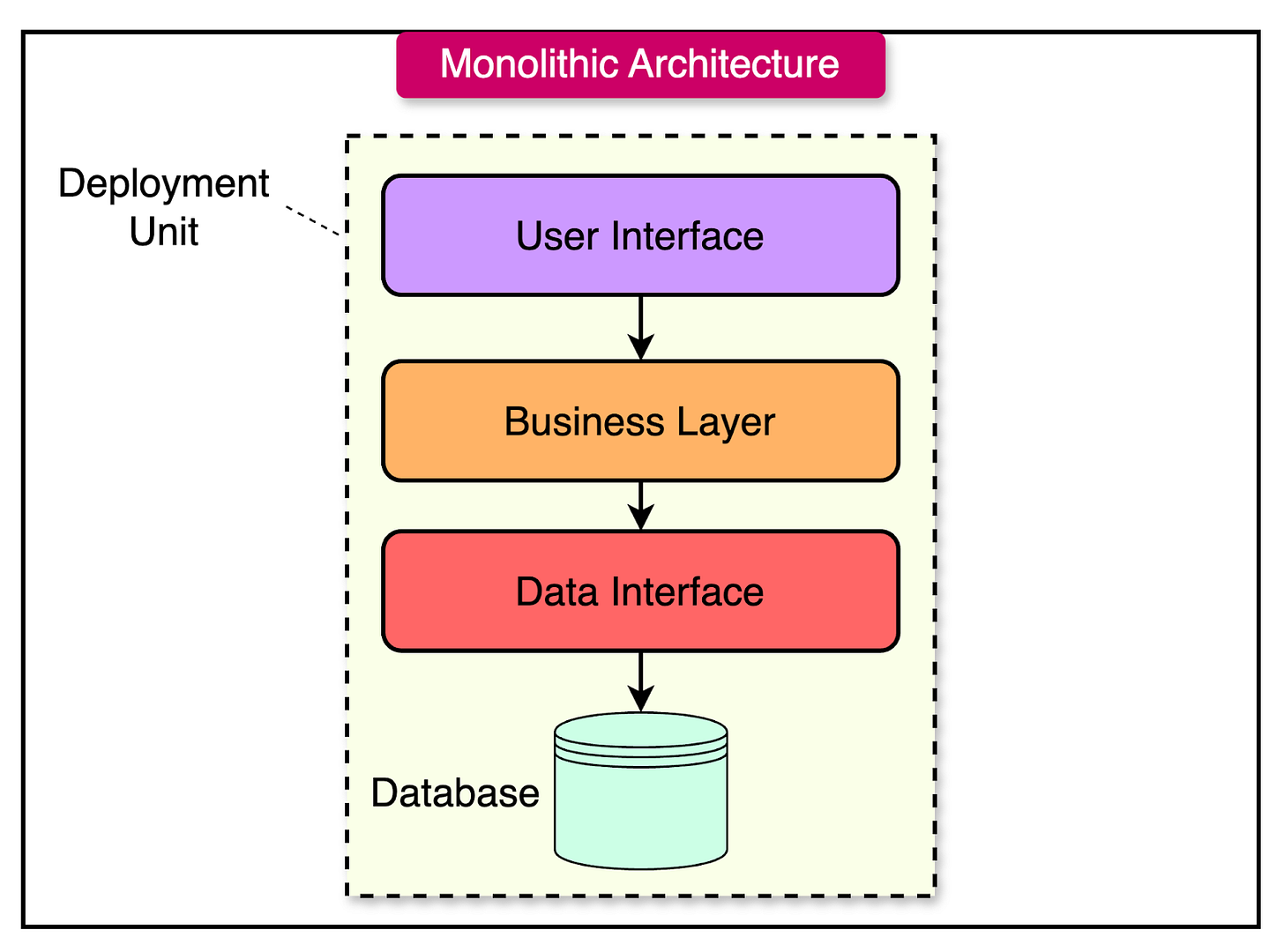

Monolithic architecture is the traditional way of building software applications, where the entire system is developed as a single, unified unit.

Imagine a software system where everything from the frontend, the backend, the database interactions, and all the supporting pieces, is packed into one giant codebase. That’s the monolith architecture in a nutshell.

[

Monoliths are a tightly connected setup where all components are woven together, running as a single, unified application. When we deploy the application, we deploy everything as one package, rather than as separate, independent services.

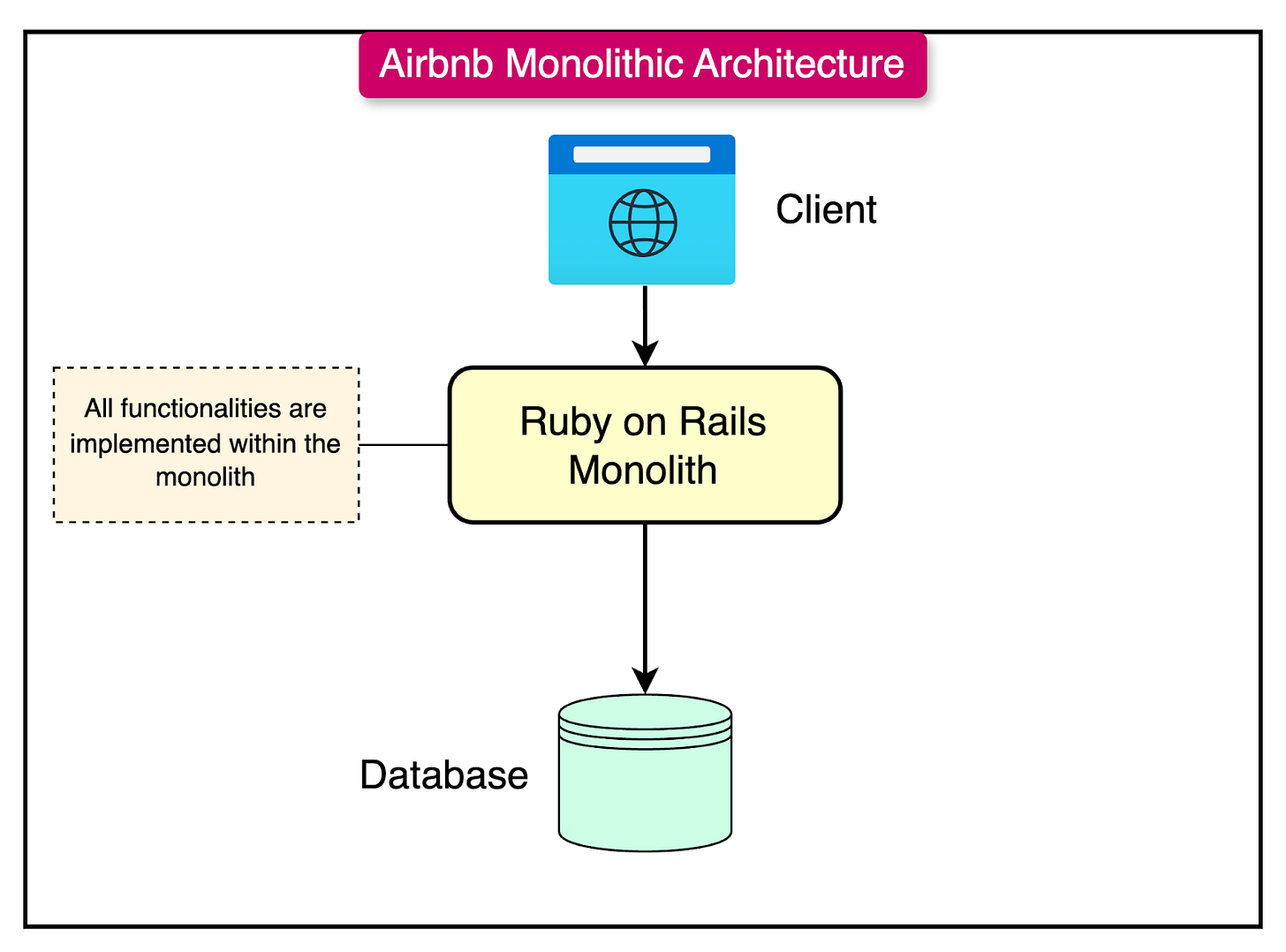

Historically, most major tech companies started with monolithic architectures before transitioning to microservices. For example, Airbnb was built as a Ruby on Rails monolith. Similarly, Twitter was also created as a monolith, but as traffic grew, it struggled with performance and scalability, leading to a migration to microservices.

See the diagram below that shows the initial monolithic architecture of Airbnb.

[

The key characteristics of a monolithic architecture are as follows:

- Single Codebase and Deployment Unit: In a monolithic system, all application logic resides in one codebase, which means all features and functionalities are developed in the same project. All developers work on the same repository, making collaboration easy in the early stages. The entire application is compiled and deployed together. If one feature changes, the entire application must be redeployed.

- Shared Database, Often Tightly Coupled: Monolithic applications typically rely on a single relational database that serves all the functionalities of the applications. This means all features read from and write to the same database tables. Strong dependencies exist between different parts of the system. If the database goes down, the entire application stops working.

- Easier to Develop Initially: Monolithic applications are straightforward to build because developers can use a single programming language and framework (for example, Java with Spring Boot, Python with Django, and so on). No need for complex inter-service communication. Also, local development and testing are simpler.

- Harder to Scale Over Time: As the application grows, monolithic architectures can become a bottleneck due to codebase complexity, deployment challenges, and scaling limitations. We cannot scale individual components independently.

Benefits of Monoliths

Monoliths have some key benefits that are as follows:

- The monolith shines because it’s straightforward to build. With everything in one place, development feels relatively easy. The frontend can call backend functions directly, often through in-memory calls within the same process, skipping the lag of network requests. There’s no need to wrestle with multiple codebases or figure out how separate services should talk to each other.

- Since the whole system is one unit, testing is relatively easy. We can fire up the application and check everything (frontend, backend, database). There is no need to mock external APIs or simulate network quirks.

- Deployment is also simple with monoliths. With only one application to push, a single command can get it live. There is no need to juggle multiple deployments or stressing over version mismatches. For small teams that need to move fast, this is gold: everyone works on the same codebase, cutting down on coordination headaches.

Downsides of Monoliths

Monoliths also have some downsides that can make them tricky in the long term. Here are the downsides:

- When traffic spikes, scaling a monolith is more like using a blunt tool. For example, if the payment system is getting hammered by incoming requests, there’s no way to scale just that piece. The entire application has to scale up: even parts that don’t need it. It’s like upgrading a whole server to handle one busy endpoint.

- Everything being so intertwined means changing one part can mess up something else. A tweak to user login logic might accidentally break the checkout flow. Every update needs heavy testing across the system, slowing things down and making maintenance difficult.

- The monolith locks the system into one tech stack. Updating one piece often means rethinking the whole codebase. Teams can end up stuck with outdated tools, unable to pivot without a massive overhaul.

Microservices Architecture

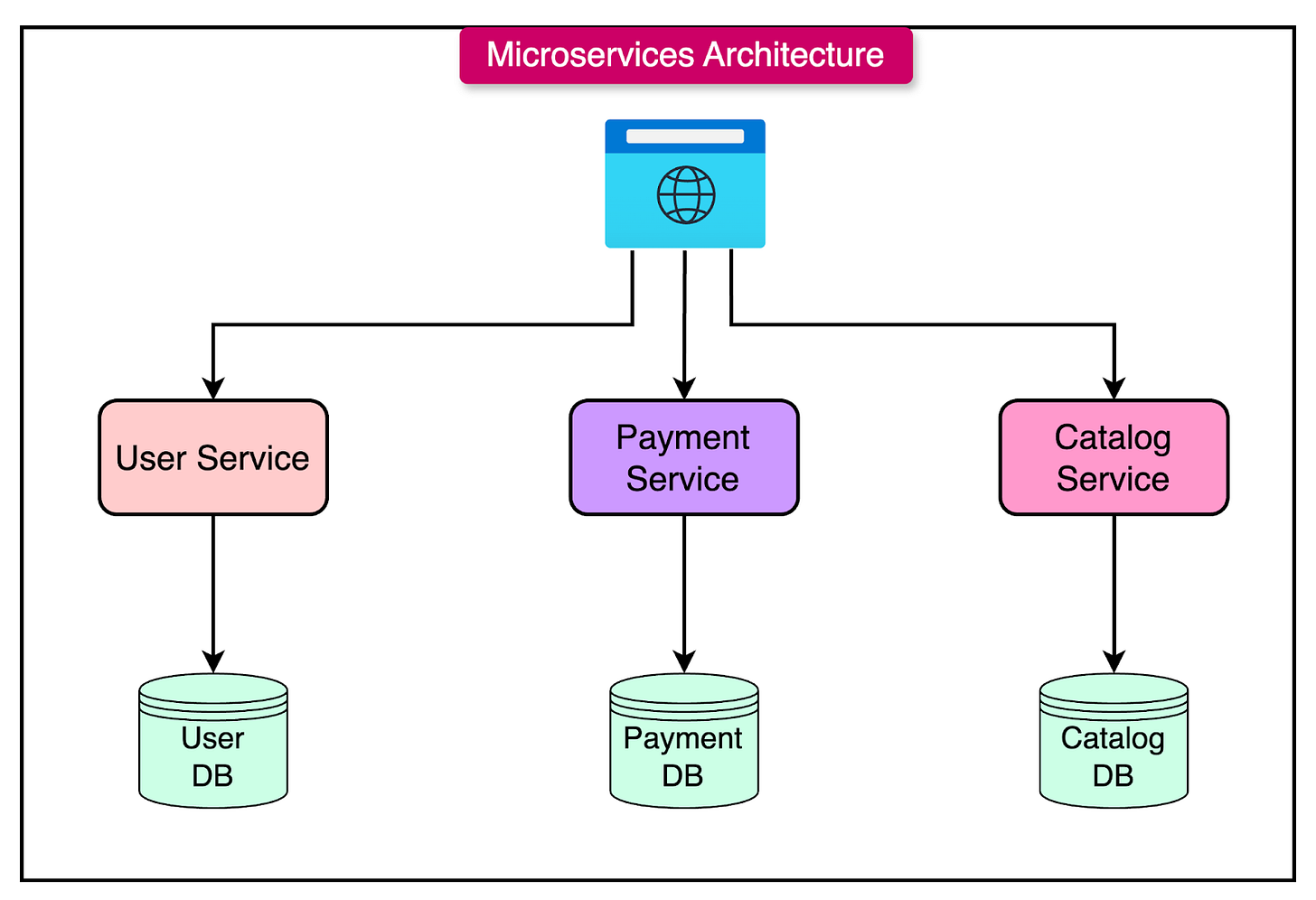

Microservices architecture is where an application is divided into multiple small, independent services that work together to form a complete system.

Imagine a large software system not as one massive program, but as a collection of small, specialized services, each designed to handle a single task exceptionally well. This is the core idea behind microservices architecture.

Instead of creating a single, all-encompassing application, the system is broken down into smaller, independent services. Each service is focused on one job, such as managing user logins, processing payments, or maintaining a product catalog. Each service operates like a mini-application, complete with its own database and deployment process. These services collaborate by communicating through defined channels, such as APIs or messages, much like how different departments in an organization might exchange emails to work together.

For example:

- A user service handles everything related to user accounts: registration, authentication, and profile management.

- A payment service takes care of transaction processing.

- A catalog service manages the inventory of products available to users.

See the diagram below:

[

Some key characteristics of microservices architecture are as follows:

- Independent Deployment of Services: Each microservice is developed, deployed, and scaled independently, meaning changes to one service do not require redeploying the entire system. Each microservice can have its database, tech stack, and runtime environment. Teams can experiment and deploy updates faster without affecting other services.

- Services Communicate via APIs: Since services are independent, they must talk to each other over a network. This happens using REST APIs, gRPC, and message brokers.

- Allows Teams to Work on Different Services: Microservices allow different teams to own and manage different services, meaning each team can use different programming languages, frameworks, and databases suited for their needs. Development can be parallelized and teams can release features faster.

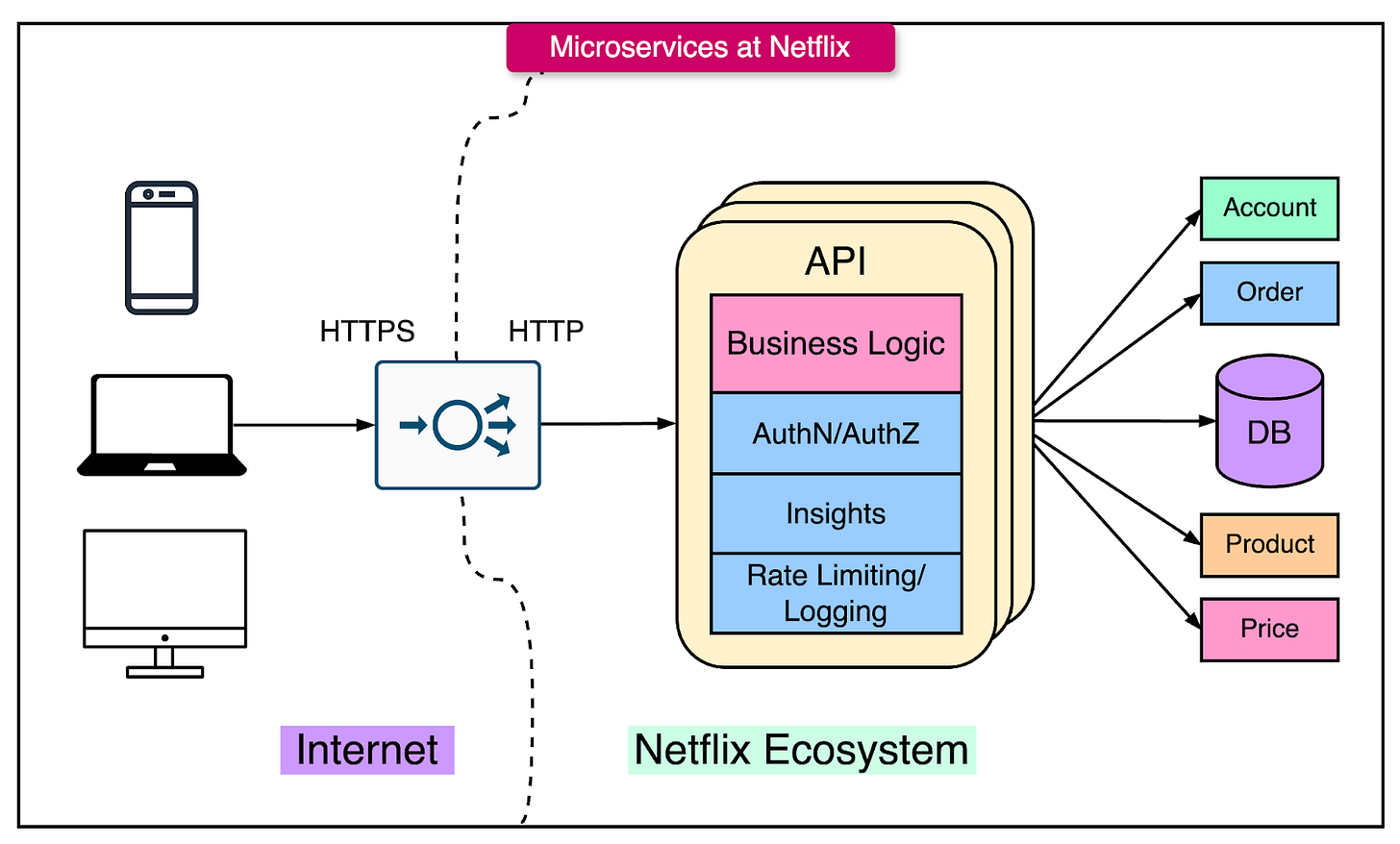

Often, companies move away from monoliths once they reach a certain growth level. For example, Netflix moved from a monolith to microservices to handle its global streaming demands. Uber originally used a monolithic architecture, but as it expanded globally, it faced scalability challenges.

See the diagram below that shows a view of the Netflix microservices architecture.

[

Benefits of Microservices

Microservices offer several compelling advantages:

- Since each service operates independently, we can scale only the parts experiencing high demand. If the payment service is swamped during a busy shopping season, additional resources can be allocated without affecting the user service or catalog service.

- Different services can use different programming languages, frameworks, or databases. The payment service might rely on a secure, robust technology, while the catalog service uses a lightweight, fast one. This flexibility lets teams choose the best tools for each functionality.

- If one service fails, the others can keep running. Should the payment service encounter an issue, users can still log in or browse the catalog while the problem is resolved. This isolation prevents a single failure from crashing the entire system.

Downsides of Microservices

Microservices come with some notable challenges as well:

- Coordinating multiple services is far more complicated than handling a single application. Each service requires its deployment, monitoring, and maintenance. Ensuring they all work together demands advanced tools like Kubernetes for orchestration and careful planning across teams.

- Running many services means more servers, more databases, and more infrastructure. Each service needs its resources, which can increase operational expenses. For smaller systems, this overhead might not be worth it.

- Keeping data consistent is tricky. If a user updates their profile in the user service, that change must propagate to the payment or catalog services that rely on it. However, the data may be eventually consistent (where updates sync over time) and this scenario must be handled as part of the design.

Modular Monolith

A modular monolith is an architectural approach that combines the simplicity of a monolith with the structured separation of microservices, without breaking the system into independent services.

Imagine a software system that retains the simplicity of a traditional monolith but introduces a level of organization that makes it far easier to manage and evolve. That’s the essence of a modular monolith.

Modular monoliths serve as a middle-ground option: an architectural approach that combines the straightforward nature of a monolith with the clarity of modular design. On a high level, the modular monolith remains a single codebase and a single deployment unit. However, within this unified structure, the system is divided into distinct modules, each handling a specific functionality, such as billing, user management, or product catalog.

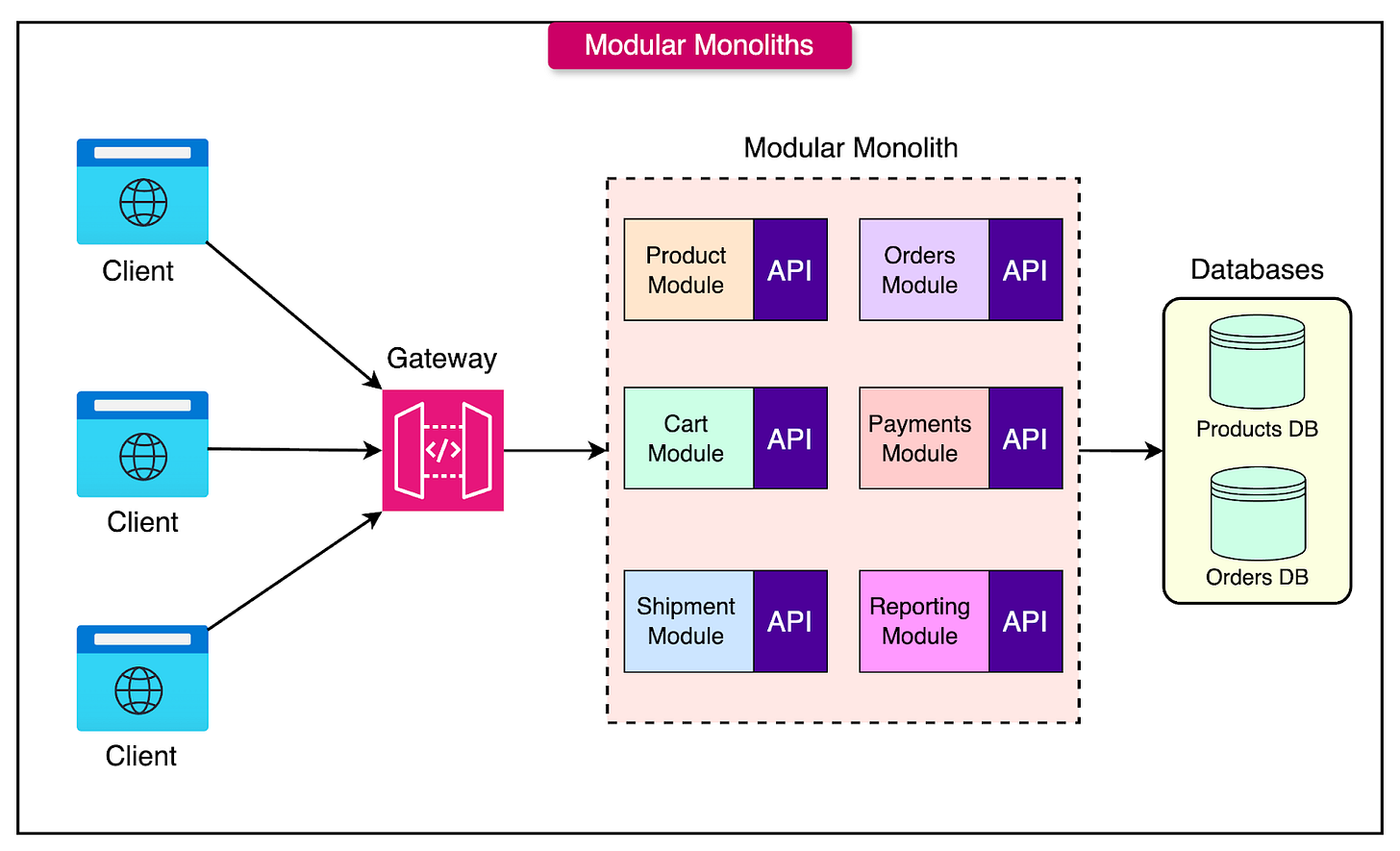

See the diagram below for an example of a modular monolith supporting multiple functionalities in their respective modules:

[

In a modular monolith, the entire application operates as one cohesive entity, but its internal structure is split into modules that focus on individual domains or features.

For instance, in an e-commerce application, there might be:

- A module for user management, handling accounts and authentication.

- A module for billing, managing payments, and invoices.

- A module for product catalog, maintaining listings, and inventory.

These modules are like separate folders or namespaces within the codebase, designed to keep functionalities distinct and minimize excessive interdependencies. While everything runs as a single system, this organization ensures the code remains tidy and manageable, reducing the tangling that often plagues traditional monoliths.

The key characteristics of a modular monolith are as follows:

- Modular Code Organization: A modular monolith is designed using well-defined modules, each handling a separate business function. Each module has clear boundaries and does not directly interfere with others. Modules communicate using internal APIs or event-driven messaging instead of tightly coupling to each other’s logic. Encapsulation is enforced, meaning each module can manage its data instead of sharing a single, massive database schema.

- Easy Transition to Microservices If Needed: The system is already divided into independent modules, transitioning to microservices is much easier. Instead of breaking a monolithic system from scratch, teams can extract individual modules as microservices over time. Since module communication is already API-based, migrating to network-based microservices requires minimal changes. Databases can also be modularized (each module having its schema), reducing dependency on a single shared database.

Benefits of Modular Monoliths

The main benefits of modular monoliths are as follows:

- As a single codebase, it keeps development, testing, and deployment processes straightforward. There’s no need to wrestle with the complexities of multiple services, distributed coordination, or intricate inter-service communication.

- The modular structure facilitates refactoring and evolution. If a specific module needs adjustment or eventual extraction into a standalone service, the clear boundaries simplify this process, making the system adaptable.

- Running a single system is generally less costly than maintaining a fleet of microservices. With fewer servers, databases, and no need for advanced orchestration tools, operational overhead remains low.

Downsides of Modular Monoliths

The downsides of modular monoliths are as follows:

- Limited Scalability: Unlike microservices, where individual components can be scaled independently, a modular monolith must scale as a whole. If one module faces heavy demand, the entire application must be scaled up, even if other modules remain underutilized, leading to potential inefficiency.

- Risk of Sneaky Dependencies: Without careful oversight, modules can become overly interconnected. Hidden links might emerge over time, where one module subtly relies on another in unintended ways. This can erode the benefits of modularity, creating a system that’s modular in name but tangled in practice.

Transitioning from One Architecture to Another

As a software system grows, the architecture we start with might not always keep up with the team’s needs or user demands. Switching architectures isn’t just about following trends. It’s about solving problems like performance bottlenecks, team productivity, or budget constraints.

Here are some common transitions with some technical insights.

Monolith to Microservices

The key trigger for moving away from a monolith is usually the system struggling to cope with surging traffic or increasing complexity within a single codebase. The signs can include performance bottlenecks during peak usage or challenges managing an expanding code structure.

For example, imagine a startup’s e-commerce app launched as a Monolith, handling user authentication, product listings, and payments. As the platform hits 10,000 concurrent users (an arbitrary number) during a sale, the system falters and payment delays drag down unrelated features like browsing.

A monolith shines in early development for its straightforward setup, but as demand grows, its limitations surface. Microservices enable independent scaling, deployment, and updates of components, offering resilience and adaptability.

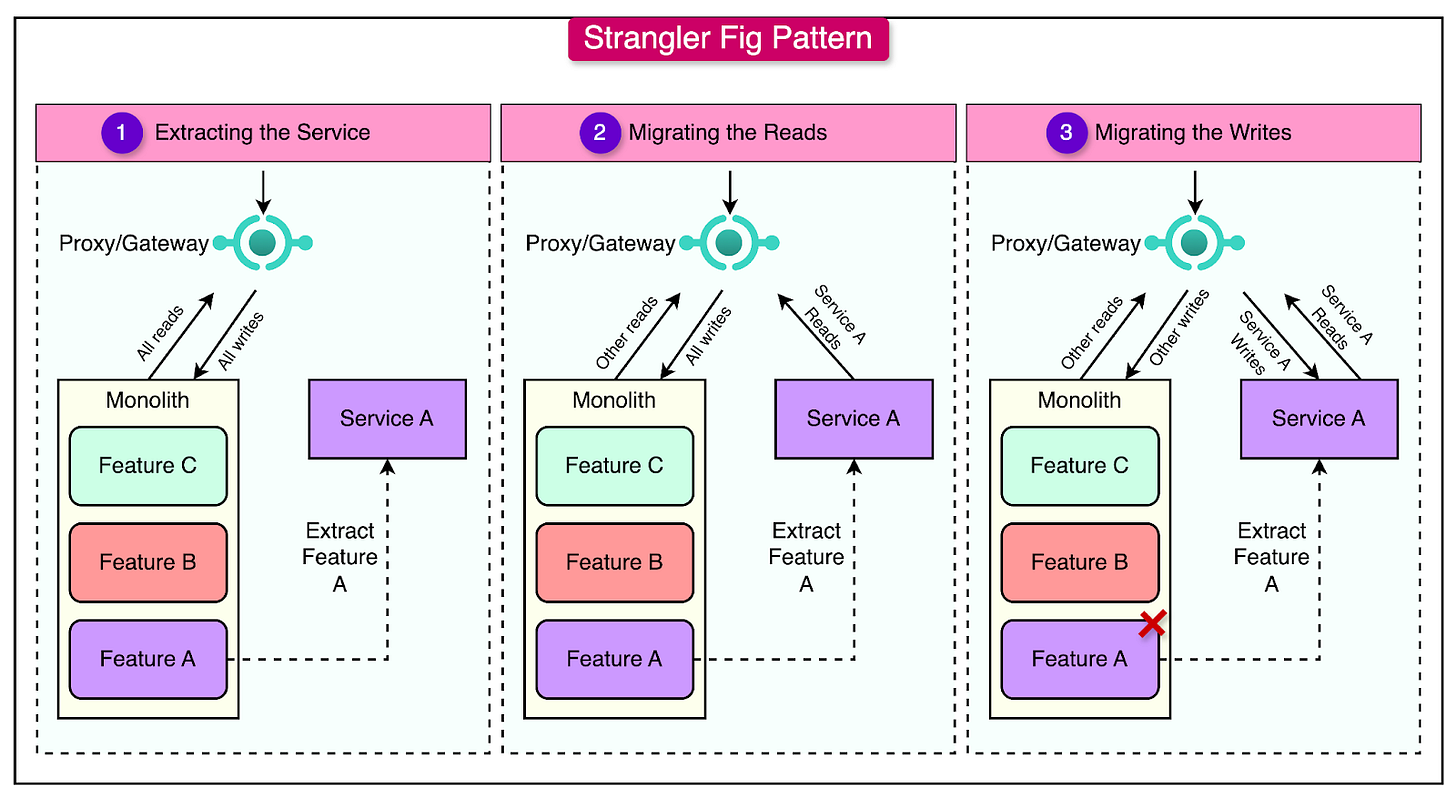

One of the most popular ways of transitioning from monolith to microservices is by using the Strangler Fig pattern as shown in the diagram below:

[

Some technical insights to keep in mind while tackling such a transition are as follows:

- Refactoring: Apply domain-driven design to carve out “bounded contexts” (for example, payments and authentication). Begin with the most strained component, maintaining the monolith for stability during the transition.

- Communication: Link services with APIs (for example, REST, gRPC) or message queues (such as RabbitMQ) to ensure loose coupling.

- Data: Assign each service its database to eliminate shared state. This may introduce eventual consistency, manageable with tools like event sourcing.

Monolith to Modular Monolith

The key trigger here is also the same. The monolith’s codebase grows chaotic, hampering development speed and risking errors. However, the team isn’t prepared for microservices complexity.

For example, a content management system (CMS) built as a monolith has sprawled over time. Adding a user management feature breaks content delivery due to tangled code. The team realizes that they need order, but microservices feel like an overkill for the small team. In such a case, a modular monolith could be an ideal choice.

Modular monoliths retain the single-unit simplicity while organizing code into distinct modules, enhancing maintainability without distributed system overhead.

Some technical insights are as follows:

- Refactoring: Split the codebase by business domains (for example, users and content), enforcing clear module boundaries using domain-driven design.

- Isolation: Limit inter-module data access despite a shared database, using schemas or namespaces for separation.

- Internal APIs: Enable module interaction through defined functions or events, avoiding direct dependencies like shared variables.

Modular Monolith to Microservices

A key trigger for this could be a specific module that demands independent scaling, deployment, or a unique tech stack due to distinct performance or functionality needs.

A modular monolith organizes code well, but as a single unit, it can’t address isolated scalability issues. For example, a logistics platform’s modular monolith may include a route optimization module struggling with real-time traffic data during peak hours, while billing and tracking remain stable. In such a situation, the team can decide to extract the route optimization feature as a separate microservice.

Some technical insights are as follows:

- Refactoring: Define the module’s boundaries and extract it with a clear external API, isolating its monolith interactions first.

- Data: Shift the module’s data to a dedicated database, syncing or migrating from the shared one as needed.

- Communication: Use APIs or events to maintain coordination with the Monolith, especially for real-time needs.

Summary

In this article, we have looked at monolith, microservices, and modular monoliths in detail.

Let’s summarize the key learning points in brief:

- Selecting the right architecture impacts how efficiently a system is built, scales, and operates, balancing simplicity, flexibility, and cost based on team needs and project goals.

- A monolith’s single codebase simplifies development, testing, and deployment, which is ideal for small teams and straightforward projects. However, it struggles with scalability, adaptability, and fault isolation as complexity or traffic grows.

- By breaking a system into independent services, microservices enable targeted scaling, diverse tech stacks, and fault tolerance, though they introduce operational complexity, higher costs, and data consistency challenges.

- A modular monolith organizes a single codebase into loosely coupled modules, blending the simplicity of a monolith with structured adaptability. However, it lacks the independent scaling of microservices and risks hidden dependencies without discipline.

- Shifting architectures addresses real challenges. For example, moving from monoliths to microservices for scalability, monolith to modular monolith for organization, modular monolith to microservices for module-specific needs.

References: